Insight — SWF’s Rite of Spring: Global Counterspace Capabilities Report Released

Thursday, April 11, 2024

If it’s April, it must be time for the latest version of SWF’s Global Counterspace Capabilities: An Open Source Assessment. Released on April 2, 2024, this year’s report was once again co-edited by SWF Chief Program Officer Brian Weeden and Chief Director, Space Security and Stability Victoria Samson and strives to provide objective coverage about what is known and, perhaps more importantly, what is unknown about major counterspace developments globally.

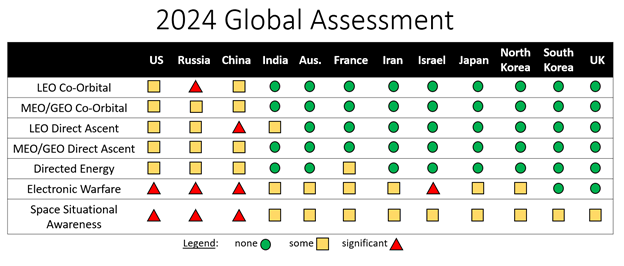

This report compiles and assesses publicly available information on the counterspace capabilities being developed by multiple countries across five categories: direct-ascent, co-orbital, electronic warfare, directed energy, and cyber. It includes updates through February 2024. In an effort to increase accessibility, translations of the executive summary will be available in May in Arabic, Chinese, French, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish.

The report is divided into two major sections. The first covers countries that have conducted destructive anti-satellite (ASAT) tests and lists them chronologically in the order in which they were first held: the United States (1959), Russia (while the Soviet Union, 1963), China (2005), and India (2019). The second section alphabetically lists countries that we have identified as having interest in or are using counterspace capabilities: Australia, France, Iran, Israel, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. It assesses the current and near-term future capabilities for each country, along with their potential military utility.

The purpose of the Global Counterspace Capabilities report is to provide a public assessment of counterspace capabilities being developed by countries based on unclassified information and to contextualize reports about the capabilities based on how they compare to what other actors are doing. We hope doing so will increase public knowledge of these issues, the willingness of policymakers to discuss these issues openly, and involve other stakeholders in the debate.

The bulk of the report highlights the efforts underway by many countries to conduct research, development, and testing of destructive and non-destructive counterspace capabilities. Many of these capabilities are similar to capabilities developed by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Today we are seeing a proliferation of these capabilities to a growing number of countries. Between 1959 and 1995, the United States and the Soviet Union conducted 50+ anti-satellite (ASAT) tests in space. Since 2005, we’ve seen 20+ tests from the United States, Russia, China, and India.

But to date, only non-destructive capabilities are actively being used against satellites in current military operations (such as jamming and cyber).

New this year is the inclusion of Israel. While we have not identified any statements by Israeli officials regarding counterspace capabilities, Israel’s demonstration of an exo-atmospheric intercept by its Arrow-3 missile defense system and its extensive use of jamming and spoofing in Gaza made it clear to us that they should be incorporated in this year’s assessment. With the addition of Israel, SWF has doubled the amount of countries it covers in this annual report: from six countries when it first started this in 2018, to 12 countries this year. This speaks to the proliferation of investment in these sorts of capabilities and how many countries perceive the need to develop them in order to protect their continued access to and use of space.

There are several other notable updates for 2024. One is the striking similarities between the robotic spaceplane programs of the United States, China, and most recently India. The US X-37B, Chinese Shenlong, and Indian Pushpak spaceplanes appear to be structured to conduct very similar missions and have similar capabilities, and also are inducing significant concerns by other countries over their potential use as weapons. As well, we discuss the extensive use of electronic warfare (e.g., radiofrequency jamming and spoofing) in active military conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza and outside of armed conflict in the Eastern Baltic, all of which is starting to impact commercial aviation. We also have information included on French plans for developing laser-armed GEO satellites and Australia’s purchase of the United States’ only acknowledged offensive counterspace weapon system, the Counter Communications System (CCS), a ground-based jammer.

One of our most important items is the tracking of how much orbital debris has been created by destructive ASAT testing. Our updated table 5.1 shows that 3,133 trackable pieces are still in orbit out of 6,863 total created by ASAT testing done by the United States, Russia, China, and India. The most recent destructive ASAT test was held by Russia in November 2021; during it, over 1,800 pieces of debris were created, of which 67 are still in orbit.

We feel strongly that a more open and public debate on these issues is urgently needed. Space is not the sole domain of militaries and intelligence services. Our global society and economy are increasingly dependent on space capabilities, and a future conflict in space could have massive, long-term negative repercussions that are felt right here on Earth. The public should be as aware of the developing threats and risks of different policy options as would be the case for other national security issues in the air, land, and sea domains.

If you would like to hear more about the contents of this year’s report, SWF is happy to announce that it will be hosting an event with our colleagues at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Aerospace Security Project, who will be releasing their excellent counterspace threat assessment as well. “Counterspace Trends: An Evolving Global Landscape” will be held virtually from 9 am-10 am EDT on Wednesday, April 17, 2024. For more information, including how to register, please visit here.

Share

Share