Could a war in space really happen?

- Published

In the past the nuclear balance between the US and the USSR helped to prevent war in space. The modern world is more complex and already some 60 countries are active in space. So is a war involving attacks on satellites now becoming more likely?

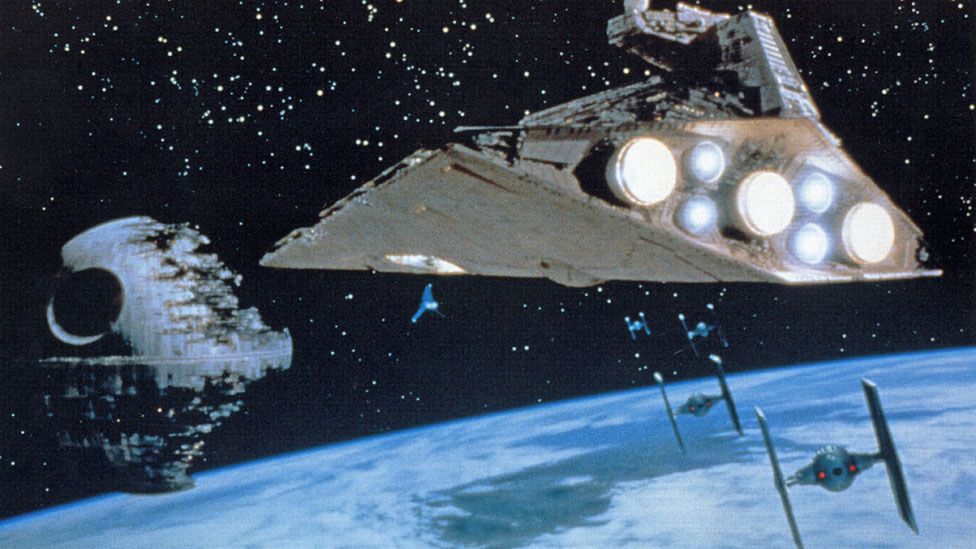

Millions have been enjoying the Hollywood version of conflict in distant parts of the universe as the new Star Wars film is released. It's enjoyable escapism - space conflict is, after all, nothing to do with reality. Or is it? According to military analyst Peter Singer of the New America Foundation, "the idea of… fighting in space was once science fiction and now it's real".

Space wars may not involve intergalactic empires or spacecraft zapping each other. If they occur they are likely to be focused on things that matter hugely to all of us - satellites.

They are more and more crucial to the way we lead our lives. They help us tell the time or draw money from a bank, or work out where to go using a smartphone or satnav.

And for the modern military too, life without satellites would be a nightmare.

They are used for targeting weapons, or finding things that need targeting in the first place. They form the US military's "nervous system", according to Singer, used for 80% of its communications. And this includes the communications central to nuclear deterrence.

There has to be an "absolutely reliable" communications channel at all times between US nuclear forces and the president, says Brian Weeden, a former US intercontinental ballistic missile launch officer.

"The thinking was you might have nuclear detonations going off and you might have to co-ordinate some kind of a responsive strike."

The satellites designed to secure these communications - and to detect any possible nuclear attack - sit in geostationary orbit high above earth in what was thought until recently to be a kind of sanctuary, safe from any attack. No longer, thanks to a Chinese experiment with a missile in 2013 which reached close to that orbit, some 36,000km above the Earth.

In a rare public statement earlier this year Gen John Hyten of US Space Command expressed his alarm at the implications of these Chinese tests. "I think they'll be able to threaten every orbital regime that we operate in," he told CBS news. "We have to figure out how to defend those satellites. And we're going to."

It's not the first time that the prospect of a conflict waged in space has suddenly presented itself as a frightening possibility.

In 1983 US president Ronald Reagan launched his Strategic Defence Initiative, widely known as Star Wars, proposing the development of space-based weapons to defend against Soviet missiles.

US President Ronald Reagan wanted to make the type of laser weaponry of sci-fi films a reality

This marked a dramatic new phase as it suddenly appeared that space power could undermine the delicate balance of superpower weaponry on earth. One Soviet response was to begin thinking about how to target US satellites in a time of war.

Bhupendra Jasani of King's College London, a veteran observer of space security, says the Soviets "actually launched an anti-satellite weapon test in orbit... they were actually playing a nuclear war scenario. That if there is a war we will knock down the spy satellites, we will knock down the communications satellites and the rest of them".

Today's China, he suggests, is thinking along similar lines.

And today's world - with only one military superpower, the US - is far more unpredictable than it was in the 1980s, according to Brian Weeden.

"There was a tacit understanding between the US and Soviet Union that an attack on specific satellites that could disrupt and disable nuclear command and control or the ability to warn about an attack would be seen as a de facto nuclear attack. That served to deter both sides from attacking satellites," he says.

"There are now more incentives for a potential adversary, such as China, to attack satellites or disable them as part of a conventional conflict [because] they know full well that space capabilities are at the core of the US's ability to project power."

In this climate of suspicion there is also a risk of accidental damage to key military satellites - caused perhaps by space junk or debris - being interpreted as a hostile act.

China's 2007 test destruction of a satellite created thousands of tiny fragments circulating in space, which could potentially collide with another satellite.

"Debris is sometimes so small you can't even track (it)," says Jasani. "So if a part of the debris hits a sensitive satellite you will never know if it was debris or deliberate. Military reaction is to take the worst case scenario - that it was hit by somebody else. And that's a trigger point."

Cyber attacks on military satellites are another concern.

Military analyst Peter Singer, who's co-written a book, Ghost Fleet, setting out how he believes a future global war could erupt in space as well as on earth, points out that this is something that many countries, or militant organisations, could get involved in.

"It's not just the big boys who can play at it," he says. "Anti-satellite missiles - that's been within the realm of great powers, like a Russia, a China, a US. It's not something that a Hezbollah or an al-Qaeda or an ISIS could pull off. With cyber warfare, the barrier to entry is a lot lower."

All this is putting under ever greater strain a system that has kept the peace in space so far.

It was widely assumed in the 1950s that space would not stay peaceful.

"We thought very seriously about possible military conflict in space," says Sergei Khrushchev, then a Soviet rocket scientist, as well as the son of the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

When he started to design the first manned space station in 1965 it was armed with small rockets and a cannon.

There were nuclear detonations in space by both the Soviets and the US and even US plans to show their nuclear strength by causing a nuclear explosion on the moon.

"The idea was that if you sent a bomb up you'd be able to see the crater that was created by the human eye on earth so it was a way of demonstrating long-range missile capabilities" says Jill Stuart, editor of the journal Space Policy.

"The whole point was to send a message to the Soviet Union, but the idea was scrapped primarily because it was felt that the American public would not support the idea of doing that to the moon".

The US opted to land on the moon instead, and space became in many ways a symbol of international co-operation, not conflict. In 1967 an Outer Space Treaty was signed prohibiting among other things the deployment in space of weapons of mass destruction.

But as satellites became ever more important - first for spying, then for weapons targeting and navigation - space has been drawn more and more into military thinking, and global rivalry.

It is a far more complex world than the 1950s and 60s. There are now more than 60 countries active in space, and huge commercial interests involved.

Perhaps, suggests military analyst Peter Singer, there will always be a tension in the way the world approaches space.

"You can engage in wonderful acts of co-operation and scientific research, and you can also still plan to beat the heck out of each other," he says.

"Space has been this realm that at least so far has not been touched by conflict. But that's not a guarantee for the future."

Listen to Chris Bowlby's documentary Space Wars on BBC World Service on Saturday 19 December. Click here for transmission times, or to listen online after broadcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.